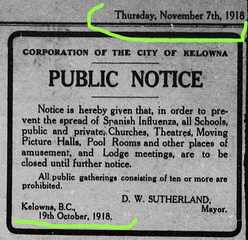

Today I broke free from imposed solitary confinement today! After five weeks in lock-down, I had my first glimpse of Level three restrictions.

Traffic was light, and my first stop was the vetinery clinic. A dozen cars were lined up in the car park, with ’No Entry’ and ‘Do Not Enter’ notices around, and tape straddling the door. A vet went from car to car, checking on barking dogs and cowering kittens. Owners stood behind their cars, fiddling with cell phones, enjoying the balmy autumn sun. I struck up a conversation with the van alongside me. It was a police dog squad van, with a copper young enough to be my grandson. He and his lovely Alsation were weary following a 3 hour hill chase to catch a ‘bad guy.’ Thanks to the tracking talent of the dog, the trouble maker is in gaol.

Eventually it was my turn. My dogs’ medicine was prepared and carried out, unbagged. We had two efforts to use the eftpos machine, with no luck. Like other customers I witnessed, we have to return or pay by some other means.

My next errand took me to Mitre 10 , to pick up a couple of large, tough bins. With my many rescued birds, I have a lot of birdseed to protect. Uninvited mice have been ‘crashing the party,’ and nibbled holes in several sturdy plastic bins, polluting and stealing bird seed. (Although my dogs and cat are great mousers, they can’t neutralize the entire crop moving in from the vineyard next door, to find new warm homes over winter.)

I would have been grateful to look around Mitre 10, and take a toilet break; but no such luck! Pallets packed high with potting mix and compost blocked much of the car park. Two unadorned tables outside the entrance was the goal to aim for, but to reach service one had to join the line, keep 2 metres apart and wait. I finally got to the front of my line, only to find that that queue was for already on-line- paid goods. Back to square one for me, and start again. The queues were decorated with orange road cones, measuring the space between patrons. One moved forward by one cone each time a customer was dealt with. What fun! It was like playground games from primary school, as we joked and moved closer to the table. My big bins were brought out and it was time to pay. But there was no Eftpos machine outside. I had to surrender my card to the shop assistant who grabbed it with a mechanical ‘hand’ to keep his distance. That wasn’t all. The young man also required my SECRET Eftpos digits! For the first time ever, I had to share that in order topay for my bins.

Next stop was my publisher’s office. I know she returned to work yesterday, on a very limited scale. No entry to her office though, we transacted our business on the footpath. I handed over my illusrations for the latest book, and beat a hasty retreat. We’ll do our continuing discussions by phone, which is more intimate that talking across the pavement.

On to the pharmacy, where yet another queue was outdoors, and the new ‘Covid jig’ began with one person going in as another came out. And a sturdy security guard watching our dexterous moves. With my lotions and potions collected, I faced my final challenge of today’s adventure. I joined the pavement line-dancing outside the supermarket. While chatting cheerfully to the dancers fore and aft, we moved along ever so slowly. I was number 15 in the queue, and I felt quite miffed when one

lady toddled from her car, came up behind the security traffic warden, snatched her trolley and entered without queueing. That’s not cricket, lady! And that was poor policing, traffic guy!

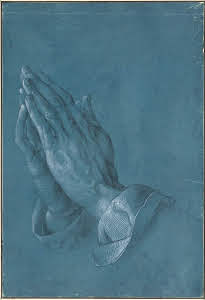

“Lord, give me patience! I need it right now!” I muttered. With my cap pulled down, glasses on, mask in place and rubber gloves firmly enclosing my itchy fingers, I trundled through the aisles with my list. Being a friendly person, utterly deprived of human contact for 5 weeks, I smiled at everyone, and wondered why no one seemed to respond. I felt invisible, until I realized that behind all that protective gear no one would have known I was smiling at them!

Those gloves are fiddly things. I’ve appreciated staff packing groceries until the Covid outbreak. I muddle along, trying not to drop things, packing like with like, dog and cat food separate from people food, chilled away from hot, etc. Meanwhile the check-out queue gets impatient waiting.

Last detour was to the petrol station. (They used to be called service stations, and they did serve. Oil would be checked, tyres pumped, windscreen washed, all for the cost of your fuel.) I shouted myself a treat; a copy of The Press, Christchurch’s morning paper which has been part of my life for three quarters of a century. I also collect old newspapers here to line the many cages and aviaries in which I care for rescued birds. At this stage I’ve got two with broken wings, a thrush with crippled legs, doves, cockatiels and a budgie who SPCA asked me to adopt when its owner went into care.

Sadly, no cheery chat with the cashier today. He’s been imprisoned behind locked doors, operating a bank-like secure money drop -box beneath a security screen.

Business transacted, money paid, change given through a two-way drawer. Now, having checked off my list of completed errands, I headed home; appreciating the loneliness of lepers and patients with contagious diseases. It is possible to feel utterly alone even with people nearby. Back home, I secured my gate and let my personal security buddies come out to play. What a joyful, waggy welcome home they gave me! I wish I was as good as my hounds think I am! They think I’m the most amazing ‘top dog’ of our pack, and the champion hunter-gatherer. I go out for a few hours and returned with enough food for a fortnight! And my reward is their slobbering, affectionate loyal protection.

We’re living through unprecedented times, with no end in sight. We are expected to adjust and adapt our personal comfort for the greater good. I am proud of being a Kiwi, and we are doing so well in protecting the vulnerable, obeying the heavy and sudden restrictions imposed. We like freedom, which our ‘grandcestors’ fought for, and which we are currently denied. While Covid may lurk around for many months more, our country is doing remarkably well to squash it every time it rears its deadly head. Let us pray about our response, exercise those character traits that God would have us live by. Those ‘fruits of the Spirit we talked about yesterday; found in His love letter, in Galatians 5. This is a time to mature these attitudes; patience, kindness, self control and perseverance.

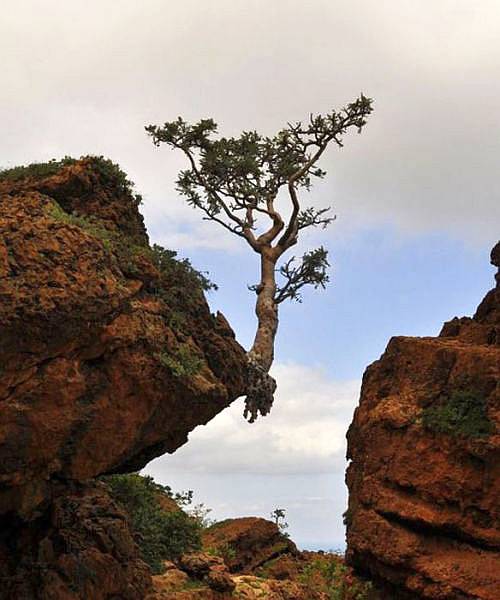

As Marlborough’s many vineyards turn golden with crinkly grapevine leaves, let’s think about the harvest of good fruit we are working on for our Master.

Rose Francis

RSS Feed

RSS Feed