Last year I researched the Spanish Flu pandemic for my family history. It seemed unimaginable that whole cities around New Zealand would be ordered into isolation, and that we, proudly, independent people, would submit to such government controls over our personal lives and hard-won freedom. Yet, last month (was it really such a short time ago?) we all obediently retreated into lock-down. We closed our work places, adjusted to home study and struggled to gain new skills using technology, to communicate and carry out necessary business. Our churches and meeting places, cinemas and concert halls cancelled gatherings. Our lives were stopped in their tracks, and turned upside down by newly enforced ways of living.

For some, this was a novel experience; for others a 'bonus' holiday from routine demands. Our priorities changed. The lowly paid and under-appreciated food providers, care workers in rest homes and communities, humble rubblish collectors, delivery and postal workers, shelf-stockers and supermarket staff were recognised as heroes. All became vital cogs in keeping our lives going. We appreciate these 'essential workers', and the courageous volunteers who have reached out to the less able in their communities, offering support with getting food and medications. I hope their contribution is recognised into the future when our lives return to a' new normal'

It will not be a 'return to the old ways., or business as usual. We will need to respect social distancing, and scrupulous hygiene for many months. Transport will be slower and probably more expensive, as arilines and shipping companies struggle to survive.

Spare a prayer for those families who will be dealing with deep regrets and unresolved grief. Many thousands of families around the world have been unable to comfort their loved ones going through the shadow of death. They have been unable to find comfort in funeralrites and family gatherings. Weddings hae been postponed indefinitely, and families split apart for months due to Covid travel restrictions. Remember too, those elderly who have little understanding of modern technology, who are truly isolated in their bubbles. Those who rely on paying bills by cheques no longer acceptable, whose cash at home is running out.

As New Zealand anticipates being lifted to Level 3 restrictions, there will be little or no change for many of us. For others comes the challenge and 'guilt' of going back to work versus staying home to supervise schooling for their young children. For many others, anxiety will increase with reduced pay or crippled businesses collapsing from the consequences of Covid's grip on the globe.

We have weathered Round One of Covid, but it's still lurking, and struggling to make a come-back. like ANZAC warriors of times past, we have to remain vigilant at our posts, have each others' backs, and obey our commanders. I'm grateful that it's a common enemy virus, not people, that we are enlisted to fight. Let's support each other in prayer, do our bit in this war effort, and continue long after wtthe threat appears to have passed; just in case.

Although the following description of that other pandemic is grim, it is true; and on the heels of Anzac Day, a solemn reminder of the horrors of a pandemic that got out of hand. May this serve to remind us how important both isolation and hygiene are in this battle for our lives. It is so eerily similar to what we are living through now, a century on.

The Spanish Flu Crisis, 1918

As World War One staggered to an end, an epidemic of influenza swept across the world, claiming an estimated 70 million lives. The following year, it disappeared. The outbreak began in the Middle East, and got its name because the King of Spain was one of its victims. A third of the sufferers experienced harsh symptoms of bronchial pneumonia, cyanosis and septicemic blood poisoning. Troops on both sides were affected that northern Spring. By Autumn, the virus spread across the Atlantic to the USA via military ships; where a brief fever overwhelmed victims. The 'flu virus caused uncontrolled haemorrhaging that filled the lungs, and patients drowned in their own body fluids.

The first Kiwis affected were soldiers of the Fortieth Reinforcement on board the troopship Tahiti. On 22 August, their convoy had called at Sierra Leone. Although none of the crew or soldiers were permitted to go on-shore, due to the Fever, locals came on board to coal up the ship. Within days, over half the men on board fell ill. The Tahiti’s final death toll exceeded 80.

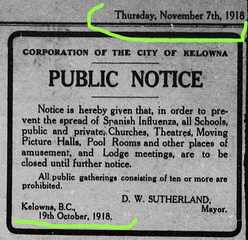

New Zealand itself was not spared. In just two months, we lost about half as many people to ‘flu as we had in the whole of WW1! By December 1918, the death toll topped 8,600; including 2,160 Maori. Military camps and central committees were established to co-ordinate relief in their areas. Each was divided into districts with a depot. Many public facilities and businesses were closed, and public events postponed. Medics were stretched, and volunteers had to fill the gaps.

The ‘flu was known also as the ‘Black Plague,’ because victims grew black spots. One hopeful remedy was for everyone, including children, to wear a camphor bag around the neck. (I remember my Grandmother kept her little muslin bag, with a camphor ball in it, just in case thedreaded ‘flu returned.)

It was believed that if the sufferer’s nose bled, he would recover. If the nose did not bleed, that patient would die. People were advised to sprinkle their fireplace with sulphur and inhale the fumes. (my grandmother still did this when, as children, we had chest infections.) She had learned this technique from her father in law, who was a surgeon in the Boer War. She also kept a camphor ball to wrap in her hanky to hopefully stave off asthma.)

Already, New Zealand was reeling from the losses of so many lives at War. Now we lost a further 8,000 people to the flu. With no vaccinations and no antibiotics available, patients struggled to breathe; thus lacking oxygen in their blood. This caused their skin to darken, and they turned purplish black post mortem. Public inhalation chambers were set up to help more people to breathe sulphur fumes, but these was not effective; and probably increased the spread of the flu. Between a third and half of New Zealand’s population was infected. Some places, especially crowded quarters like military camps, suffered losses of about 80 per cent.

Medics returning from War fell ill; medical supplies ran low. Hospitals were full, and emergency hospitals were set up in schools, halls and tents, manned by inexperienced volunteers. The healthy few manned soup kitchens. The Red Cross trained girls and women in a three-month ‘crash course’ of home-caring for victims.

By this stage, normal life was impossible. Workplaces and schools were closed, shipping around New Zealand was halted, leaving many towns short of basic supplies like flour and coal. Proper funeral services were impossible as undertakers and grave diggers were ill. Then, miraculously, by December, the worst of the epidemic was over.

The flu had killed 6,413 New Zealanders, including soldiers. It was the world’s worst recorded pandemic of flu. In four months, it had killed 25 million people; twice the number killed in fighting World War One.

This 'Flu Epidemic led to the New Zealand 1920 Health Act; a major reorganisation of manpower and supplies for pandemic management.

Lest we Forget!

Our future is in our hands, Kiwis. Please continue to trust God and encourage each other as we prepare for a gradual lifting of restrictions. "This too, will pass."

Kia Kaha!

Rosemary Francis.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed